ARTICLE: Escaping the thick soup of hyper-individualism

At the beginning of February, documentary maker, Adam Curtis, was interviewed for the BBC’s ‘Headliners’ podcast. He was there to discuss his latest set of films Traumazone, which is on iPlayer and documents the fall of communism, and democracy, in Russia. Traumazone is fascinating, and the interview is great too, but the passage I’ve transcribed below (hopefully accurately), is bigger picture than Russia. Here Curtis talks about imagination and dreams (the lack of them), nightmares and apocalysing (their rise and effect), and self-consciousness and individualism (and how they immobilize us). I’ve listened to this passage 6 or 7 times, it's a useful diagnosis, more from me on that follows. If you’d prefer to listen to the passage it runs from 17m28s to 22m38s, alternatively you can read it here:

When you don’t dream anymore, what you are in is a society without imagination and I think that’s the really powerful moment, it’s when you realise that you can’t imagine anything else. And it is very interesting that a lot of the art and novels of our time are about people with a failure of imagination, they can’t find their way out of this, and I think that’s why there is so much dystopia around; they cannot imagine anything other than this. I don’t think it will last, but we don’t dream anymore. To go back to what you said about my previous thing [The Power of Nightmares], we have nightmares and nightmares have become a sort of substitute dream at the present moment, so we imagine the worst and when you imagine the worst there is no limit to what you imagine. I think that is the problem. If you have politicians who don’t believe in anything any longer, they fail in one of their most important jobs, which is to give what happens a sense of proportion. I think ever since 9/11, our politicians, and us journalists, have begun addicted to apocalyptic crises, we really have, and what we lack – because we don’t have dreams and imaginations of what alternatives could be, which could be a benchmark against which we measure the apocalypse that hits us – we tend to imagine the worst and then when the worst doesn’t happen we feel lost. Politicians have to dream about the future, they have to give us ideas, they have to make us safe, but what politicians also need to give us a sense of proportion of the events, that’s why I made The Power of Nightmares. I felt that although there was a serious threat of terrorism in this country and in the West, it was not on the scale it was being described as by many of my colleagues, who were portraying it as an apocalyptic threat that was going to bring down Western civilisation – if you think back to that time, that is what was being told, and it had run out of control. To go back to your question, when’s that moment? It’s when there’s nothing to put something in a sense of proportion it runs out of control, either into a dark nihilism, or into a hysteria, and we get hysteria after hysteria after hysteria and we become addicted to it, we really have. I know it from my journalistic colleagues, they would never admit it (and I feel it myself as well), when a crisis comes along you apocalize/apocalypse it and you sort of want it because it fits the frame you’ve got used to, because no one is imagining anything else, so you let the worst run away with itself.

Are you suggesting then that the younger generation, which is supposed to be the generation that generates hope, are bereft of hope?

I think they feel that very deeply. Have you read the novels of Sally Rooney? She’s really interesting, she is sort of almost the realist of our age. What she describes is Gen Z, or Millennials, I don’t know, they’re on the cusp of those two, they desperately want to do something radical, they really want to change things, but they don’t know how to do it and it’s because they are so self-conscious, and that’s the really interesting thing of our time. This goes back to… I made a series called Century of the Self, which is about the rise of individualism in the West, which is a very powerful force and tends to eat away at mass democracy because everyone wants to go their own way. But it also brings with it a self-consciousness, an awareness of yourself – you only have to look at people doing selfies all the time to realise that sense of being looked at and measuring yourself, as if someone was looking at you, I think that is very deep in our society because of the rise of individualism. The characters in Sally Rooney’s novels epitomise that self-consciousness, they’re so desperate to want to change things, but because they are so self-conscious, and so self-aware, they’re almost like frozen. So in answer to your question, I think people do want to change the world but (a) they are not offered any alternative ideas by a system that has got obsessed with apocalypse and obsessed with doom, but (b) at the same time they are their own worst enemies because they are so self-conscious, so self-aware, they are almost frozen in immobility.

I am trying not to portray this as a terrible thing, but it’s got to be broken through, that self-consciousness, if you want to change the world. You have to give yourself up to something that you think is bigger than yourself. At which point, it becomes not only hopeful, but exciting. Sally Rooney’s novels are very interesting, they are very like the novels that were written at the end of the 19th Century, just before the Russian revolution in Russia, a whole class frozen, knowing they want to change things, but not knowing how to do it, and I think that’s the realism of our time.

---

Firstly, I agree with what he’s saying about journalists and politicians and their failure to give us a sense of proportion of events. I don’t however think they are always over-emphasizing, as Curtis implies. In an equally problematic way, they under-emphasize crises too – climate change being the most obvious example; it is being downplayed, COVID-19 was initially, and catastrophically, downplayed too. But his point stands, there is a lot of unwarranted hysteria and we are a little bit addicted to it; it’s clearly not healthy for individuals nor society.

The crux of what he’s getting at here, however, is the question of whether we are frozen, and if we are, why? The diagnosis – a lack of dreams and the crippling effect of individualism – feels about right. What Curtis doesn’t offer (it’s not his style) are suggestions on how to overcome these problems, how to move to a mobile, changemaking state. Educators clearly have a role to play here, and what Curtis’ diagnosis does for us is provide us with two vital areas of focus: imagination and individualism, we need more of the former, less of the latter.

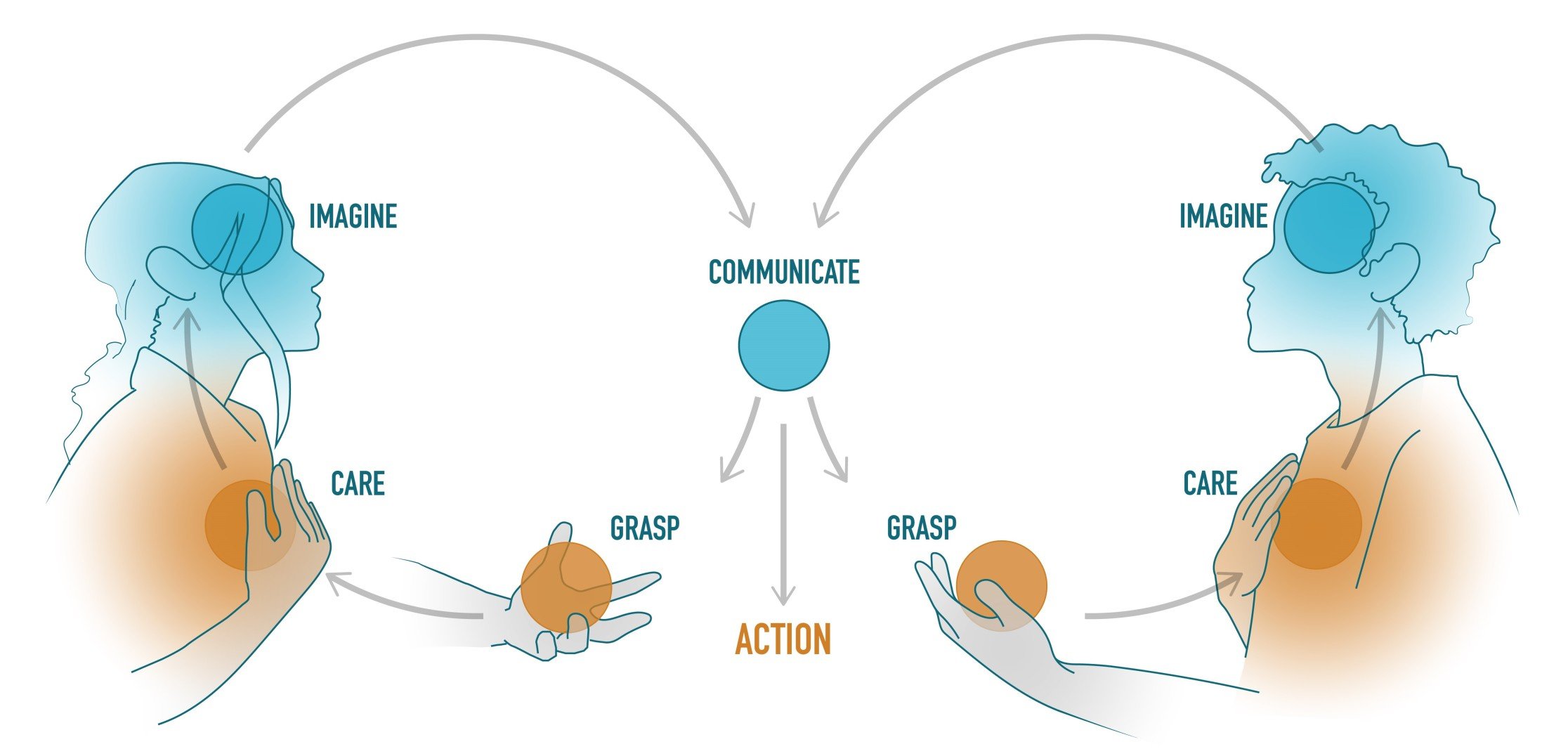

The model of education Peter Sutoris presents in his latest book ‘Educating for the Anthropocene’ is cause for cheer on imagination, he gives it the prominence it needs as one of the five ingredients of education in his wonderful cyclical model that we have adopted at Global Action Plan – it appears in our soon to be published Generation Action strategy.

Peter Sutoris and Nuith Morales (2023)

The Moral Imaginations movement, founded by Phoebe Tickell, is a great place to start to learn more about how and why to nurture imagination. This passage, from their website, stresses the vital role imagination must play:

The world we are working to manifest into reality doesn’t exist yet. We must inhabit that space with our imagination, feel it, dream it, and then bring it down to ground it in reality.

The practice is to be able to find our way into these other-worlds, and practice perception through new eyes that we wouldn’t normally have access to. Just like in a lucid dream, there are methodologies that allow you to trigger your entry into a lucid dreaming state. Just like in a lucid dream, maintaining that state takes rigour, focus and practice, and doesn’t always work.

---

There are many many ways to nurture imagination, (and you can use your imagination to dream many more up). Failing that, do an internet search, you will find a lot of advice and resources that suit different ages and contexts.

I find it relatively easy to imagine an education system that prioritises imagination and treats it like a muscle that needs regular exercise and an outlet via communication and collective action (as per Sutoris’ model). What I find harder to imagine is a society that is no longer individualistic. This is perhaps because I don’t think individualism is wholly bad, what’s bad is hyper-individualism, which seems to be the state we’re in. Here’s a short extract from my book on this:

Many environmentalists see individualism as a barrier to the sort of collective action that the climate and ecological crisis demands of us. Collectivism, however, is something individualists fear - it is a ghost from the past and they defend individualism as a safeguard against it. These are the tensions that exist – they have been there for centuries – but right now, belief in the individual as the unit of greatest importance is stronger than it has ever been. Individualism is far from perfect – it can mutate into toxic selfish forms – but it does still have merits, for example: freedom of expression, creativity, autonomy, and various other forms of liberalism. These are worth defending, and people do - most arguments and injustices can be traced back to one individual’s pursuit of freedom clashing with another’s. But this is not inevitable.

It pays to remember that today’s version of individualism is in its very early stages, it has a long way to develop. If it were a human being, it would be a toddler. Right now, it is as likely to display acts of deep and authentic compassion, as it is to throw a massive temper tantrum. But one thing individualism is not doing, is going away. The question is how will it mature? Will individualism grow up to be an unruly teenager and dysfunctional adult? Or will it blend in some way with collectivism, so that individuals can simultaneously identify as a unit of one, and a unit of many? Deliberative democracy is growing in popularity around the world, this is a very promising sign. Individualism and collectivism could find a way to merge into one another.

---

The toxicity of hyper-individualism is not going to go away on its own, not when there are so many institutions – not least the formal education systems of many nations – that champion and reinforce individualism in conscious and unconscious ways, and businesses that profit from it. A lot of work needs to be done, self-interest values (clustered in the bottom left of the Schwartz values map) need to be weakened, while bigger than self values (top right) need to be strengthened. There are ways to do both these things, especially in a school environment, just as there are ways to nuture the self-direction values (top left) and weaken tradition and conformity values (bottom right). Do please get in touch to talk more about this.

Schwartz theory of basic human values (1992)

The last thing I'll say on this (for now) is that I don't agree with Adam Curtis that young people are their own worst enemy, it is not their fault that they are as self-conscious and self-aware as they are. Young people swim in a thick soup of hyper-individualism; the enemies (their enemies) are those who are cooking up the soup. There are individuals and institutions who deliberately activate and reinforce feelings of self-consciousness for profit, power, or political gain. One of our most important roles as educators, therefore, is to help young people understand self-consciousness, its roots, how it is reinforced, and how to overcome it personally and collectively to become unfrozen.

Sally Rooney’s novels aren’t necessarily age appropriate for school students, but there are plenty more novels, documentaries, and films that explore these issues that could be put onto local and national curricula. There are also schools programmes, like the Dirt Is Good Project, that diminish young people’s feelings of self-consciousness about doing good – it is having powerful proven effects, we’ll be releasing our latest research findings on this soon.