An education system in need of a purpose

I attended Education Renewed last week, in London, an event co-hosted by the NEU and Teacher Tapp. It was great to be invited, both personally, and because its good to know there's a place for environmental educators at these sorts of gatherings these days.

I got to participate in a session facilitated by Mick Waters, and it didn't disappoint. There were thirty or so people in the room, charged with looking at 'Education for the future: principles for curriculum and assessment'.

In that session there was a general consensus that the education system in England is an education system in need of a purpose. That feeling was, I suspect, also shared by the majority of the hundred or so other attendees at Education Renewed. Indeed, it is a fundamental question that resonates far and wide in England, especially in the schools system: what is the point of all this education?

In its current state, the education system in England doesn't have an explicit named purpose, but implicitly - at a societal level - it is probably something like this: the reproduction of the society and economy that it is, itself, a product of.

In other words, it is there to sustain/grow the competitive, hyper-individualistic, hierarchical, consumer capitalist, neoliberal society and economy we live in; it is not a challenge to it. This societal purpose is so rarely spoken of it has, perhaps, been forgotten that education systems can even have a societal purpose.

As a result, the purpose of education seems today to be nothing more than to prepare individual young people to survive and thrive in a neoliberal world. From listening to the stories of teachers, parents, and thought leaders at Education Renewed, this is what gets educators out of bed in the morning (whether or not they like the neoliberal world is besides the point).

Educators care deeply about their students, and their student's life chances. They are doing everything in their power to ensure that their students are ready for the world they'll enter into upon graduation. The 'end of history' theory being that no other type of world is possible.

However, I think it's fair to say that there are a lot of people (within and beyond education) who are disillusioned with neoliberalism and the neoliberal world. We are fed up and troubled by the status quo. Or, more precisely, we are anxious about its symptoms - we are feeling them. Amongst other things, we are increasingly experiencing the effects of inequality, climate change, poverty, racism, neo-colonialism, the demise of democracy, and fearing the rise of fascism - all of this and more is taking its toll on our mental and physical health.

The 'we' I speak of? The liberal middle classes, including the upper middle, the more privileged in our society - me. We are starting to feel the collateral damage of neoliberalism in ways we hadn't to date - the downsides are no longer only being felt by those with less privilege.

Liberalism and neoliberalism - not the same thing and not the answer

For a time, liberalism and neoliberalism fed off each other, what we are perhaps witnessing now, as neoliberalism deepens and accelerates, is a painful unmasking of the differences between neoliberalism and liberalism. The differences have always existed but, until now, they hadn't revealed themselves quite so obviously, at least not to the comfortably off.

Ever since the birth of neoliberalism (in the late 1970s), classical liberals have incrementally given neoliberals more and more slack. Now, in 2024, we have reached a point where it is clear that neoliberalism has been given too much slack, far too much slack.

Whilst focused on the pursuit of individual freedoms, liberals have allowed neoliberals to co-opt liberal ideals of freedom to justify and accelerate the pursuit of market freedoms. Neoliberalism has built an illusion that individual freedoms and market freedoms are two sides of the same coin. Regrettably, they're not.

As markets have become more free, individuals have - in important ways - become less free. We are less free from the damage wreaked by businesses who, having been freed to act - more or less - as they please, do just that (and to hell with the consequences).

Examples of this abound in my field, environmentalism, but to take an example from education we can look at how neoliberalism has shaped our schools over the last four decades. Mick Waters and the late great Tim Brighouse make clear in About Our Schools, that during the neoliberal age, we have seen the steady centralisation and marketisation of education. This, in turn, has led to a heavy culture of managerialism and with it a curtailment of teacher and learner freedom. This is highly damaging at an individual and societal level and, if it isn't a significant factor in the teacher recruitment and retention crisis, not to mention the pupil attendance crisis, I'd be astonished.

In wider society, businesses freed of red tape and regulation have been allowed to exploit workers, accelerate income inequality, and pillage and pollute our rivers, seas, land, and atmosphere - taking us to the brink of global climate and ecological collapse.

And so, thanks to nearly fifty years of aggressively pursued neoliberalism, a dangerous, imbalanced world has emerged; it is riddled with gargantuan overlapping crises. Still though, in policymaking circles, two and two have not yet been put together. Liberal politicians (the centre left) continue to believe that these crises can be solved from within neoliberalism. Ideologically, they remain firmly wedded to it; they don't see neoliberalism as the problem, they are deluded.

The inadequacy of liberalism in the face of the crises we are confronted with has been exposed most obviously by climate change. It is a crisis that liberal politics has spent three decades trying solve, but has utterly failing to make any meaningful progress. Chris Shaw makes this point forcefully throughout his book 'Liberalism and the challenge of climate change', summed up by this passage:

Liberalism is now destroying the foundations of life by creating a world where limitless desires can be fulfilled through the marketplace, with access to capital the only constraint on consumption... All liberalism can offer in response to the encroaching biospheric terminus is technological tinkering to maintain the 'the energy services essential to modern civilization' (Davis et al., 2018).

'Tinkering' will not solve the climate and ecological crisis (or as Katherine Burke describes it, 'the Earth crisis'), will not be solved from within neoliberalism. Nor will many of the other crises we face - a point being made ever more forcibly, by ever. more. people.

And yet, whether driven by a lack of will, a lack of understanding, or a lack of imagination, our biggest political parties continue to tinker, or promise to tinker, (as evidenced in the UK by a wholly underwhelming set of general election manifestos.) Their goal, it seems, is to merely lessen the intensity of the problems neoliberalism creates, to reduce harms back to tolerable levels - tolerable to the middle classes. That is the extent of their ambition. These parties - the parties of the centre left and centre right - are categorically not casting around for alternatives to neoliberalism. They seek only to moderate it, and refuse to blame it for any of the world's woes, not even the rise of the far right.

Parties and governments that are further to the right, or of the far right, are even more dogmatic, they are doubling down. Neoliberalism is sacrosanct to them, it is an undemocratic project that dovetails with their authoritarian and fascistic ambitions. When they're not busy denying the multiple crises we are facing, they are refusing to blame neoliberalism for them; and they accuse anything that looks like an attack on neoliberalism as an attack on 'freedom'.

To the left of the centre left, we find marxists, socialists, and social anarchists; they are seeking alternatives to neoliberalism. Where possible - mostly at very micro levels - they are attempting to pre-figure these alternatives too; to bring them to life. They are running communities, businesses, NGOs, education settings, protest movements, and - in the case of Rojava - entire regions of a country, in ways that they'd like the wider world to be run. Success is patchy, but noteworthy, especially given a context where neoliberalism has assumed an almost global hegemonic status.

Pre-figurative politics, is not - however - an exclusively leftist pursuit. Which brings us back to the purpose of education.

Pre-figurative politics and the English education system

The education system in England today is polarised. Our schools lie somewhere along a spectrum, but it seems to be getting longer each year - the distance between one end and the other keeps growing as the overall purpose of education becomes less and less clear.

At one end there are schools run by all powerful, authoritarian, leaders who treat children as subjects to be controlled. They declare that this treatment, while seemingly harsh and highly restricting, is for their own good. Their students achieve success, but it is success against and ever narrowing set of mainly academic criteria. These are neoliberal, as opposed to liberal institutions.

At the other end are schools who treat children like individuals. Here democracy is cherished, children's voices are valued, as are the voice's of parents and teachers. These are compassionate, inclusive, diverse, collaborative, and complex (in a good way) education settings. Children and teachers are given much freedom, agency and autonomy. They are engaged in mutual processes of self-discovery and discovery of the world. They are nurtured to grow and mature into the people they want to be. Students can and do still succeed against the narrow set of criteria imposed by national policymakers, but they succeed more broadly too; they leave school as rounder human beings, they are truer versions of themselves. These are liberal, as opposed to neoliberal, institutions.

The purpose of education in authoritarian schools seems to be preparation for ever more extreme versions of neoliberalism. The schools themselves have cultures that match the world of accelerated neoliberalism. They emphasise competition, individual success, strict hierarchy, and compliance. There are winners and losers; they are pre-figurations of a neoliberal, authoritarian, world.

In democratic schools the broad purpose is, perhaps, to defend democracy. But the project is a mainly liberal one. Liberal schools are, in essence, individualistic places - children are being nurtured to be their best selves, they are being prepared to thrive as liberals in a neoliberal world. But in the age of accelerated neoliberalism, opportunities for liberalism (in the classical sense) are diminishing, it is a way of life that is fading away, and fast losing its lustre and legitimacy. This begs the question: should schools at this end of the spectrum be pre-figuring something that is ceasing to exist?

Most schools sit somewhere between these two poles, but over the last decade, we have seen the scales tip towards the neoliberal, authoritarian, right. We can expect Kier Starmer, should he come to power, to attempt to tip the scales gradually back in favour of liberalism and the promotion of liberal values.

Both ends of this spectrum are problematic, and most schools try to avoid the extremities. It is unclear, however, if being in the middle of this spectrum is a good place to be, it might be the worst of both worlds. A third magnetic pole to draw schools away from the liberalism / neoliberalism axis might be what's needed. We might need schools that have a grander societal purpose than the perpetuation of neoliberalism.

A crisis of confidence, ambition, imagination?

Earlier in this essay I argued that - generally speaking - society today sees the purpose of education as nothing more than an exercise in preparing individual young people to survive and thrive in a neoliberal world. This was evident at Education Renewed, and is echoed across the education sector (from right to left).

At Education Renewed we heard from YouGov whose recent polling of parents revealed that when asked about 'the main purpose of education' by far the most commonly selected response is 'to develop children's knowledge and skills (72%)', followed by 'helping children to develop a love of learning (47%), socialise and make friends (40%) and prepare for the world of work (38%).'

The summary report YouGov gave us at Education Renewed did not make it clear whether parents were given the option to select a societal purpose, e.g. 'to prepare young people to take collective action for the good of people and planet' (which - incidentally - is the goal of the Generation Action team I lead at Global Action Plan). I don't think the were. It is as if society is either content with neoliberalism (which I doubt), or lacks confidence in the ability of the education system to do anything about it.

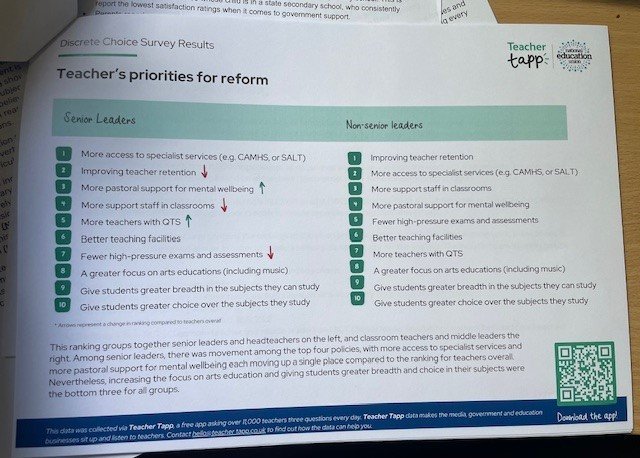

We also heard from Teacher Tapp, they had given teachers a list of ten potential action areas and asked them to rank them in order of priority when it comes to education system reform. Again, the list of options provided is more revealing than the rankings the teachers came up with:

Teacher's priorities for reform - Teacher tapp, June 2024

The list and how it has been ranked speaks to the funding crisis we know is hitting schools so hard right now, but it also reveals how inward looking the education sector has become. The bigger questions about why we educate young people aren't being explored, at least not on this evidence.

Fewer people than ever seem to see education as an instrument of change, or a tool to be used by a governments to effect a transformation of society or the economy. The idea that it might be has been marginalised. Is this another indicator of a crisis of confidence, or of a lack of ambition and imagination (this time from within the education sector)? Or maybe, the education sector has been conditioned into thinking it's sole focus should be on individual, not societal outcomes? It could also be that schools and teachers don't feel they have a mandate (or permission) to pursue societal objectives?

Despite all this, it is unquestionable that the education system can and does have an impact on more than just the individual. It is both shaped by, and a shaper of, our societies - whether it intends to be or not. Given this, we have to consider the impact of our education systems on society as well as on the individual - for it can have a transformative impact on both (and not necessarily in a healthy direction, it is not a benign force as I've argued elsewhere).

The extent of the Earth crisis, and the impotence of liberalism when it comes to dealing with it, forces us to think again about societal purpose. We need to ask ourselves how the education system can help solve the wicked problems of the world?

Education beyond the end of history?

In chapter two of 'Renewing public education' (not related to the Education Renewed event), the FORUM board make this provocation in their discussion of the societal purpose of education:

Education today ought to raise consciousness of the exploitative nature of neoliberal capitalism, the social system which characterises our society. Without this consciousness, inequality becomes naturalised. It is seen as an inherent element of the human condition rather than the product and consequence of a particular ideology. Consciousness is a precondition for the possibility to act for change. Mass formal education has the potential to maintain and reproduce the status quo and so continue the entropy that we observe in modern human societies, or to work against this and enable people to flourish.

One could substitute 'climate change' for 'inequality' in this paragraph, and 'the planet' for 'people' in its final sentence. Despite this plea, education today does not 'raise consciousness of the exploitative nature of neoliberal capitalism'. It won't do this because those who control education policy do not see neoliberal capitalism as exploitative, they still see it as liberating. As stated above they are not casting around for alternatives to neoliberalism, they are trying to manage its symptoms while leaving it in tact. For now at least.

What fascinated me at Education Renewed was that when we got onto the topic of the purpose of education, the room jumped to the question of how to come up with a purpose, rather than what the purpose might be.

Process is important, but so are opinions and I wanted to hear them. Deliberations on the purpose of education should be happening at events like Education Renewed. However, despite the recognition and heartfelt frustration about the absence of a clear purpose for education, there was a reluctance to actually discuss what the purpose of education should be.

This is understandable, it is political question, it takes us into the domain of the existential. Asking oneself 'why do I teach?' and 'what is this all for?' is daunting. Those who ask it, particularly those who are conscious of the exploitative nature of neoliberal capitalism, can end up heading for their school's nearest exit door.

And so educators are left with the hidden, implicit, purpose - the reproduction of neoliberalism - and try to kid themselves that young people can survive it, even thrive within it. They will continue to do this (to have to do this) until political leaders emerge who are willing to call time on neoliberalism, willing - in other words - to respond to the IPCC's conclusion that:

Targeting a climate resilient, sustainable world involves fundamental changes to how society functions, including changes to underlying values, worldviews, ideologies, social structures, political and economic systems, and power relationships.

[Again we can substitute words here, we could replace 'climate resilient, sustainable' with 'equal and equitable'.]

If the political will to set out on a change programme as fundamental as this were to emerge (and it does need to, look at the graphs), we could expect the government of the day to grab at every tool it has at its disposal. Education is one such tool, a potentially very powerful one.

If education was tasked with helping to design, implement and sustain fundamental change, it would certainly then have a purpose to grapple with! Education systems wouldn't just need to be reformed, they would need to be re-imagined entirely. Education would be the soil from which a new society is grown - it would take us beyond neoliberalism, beyond the end of history.

It's time, I think, for a conversation about the societal purpose of education, neoliberalism won't last forever.

For more on what it means to instrumentalise education in the pursuit of a societal objective, please read Power, Purpose and Preparation, part of Global Action Plan's collection of essays on Environmentalism in a time between education worlds.